Teju urged us to "speak in the ideological name of Africa"

Interview

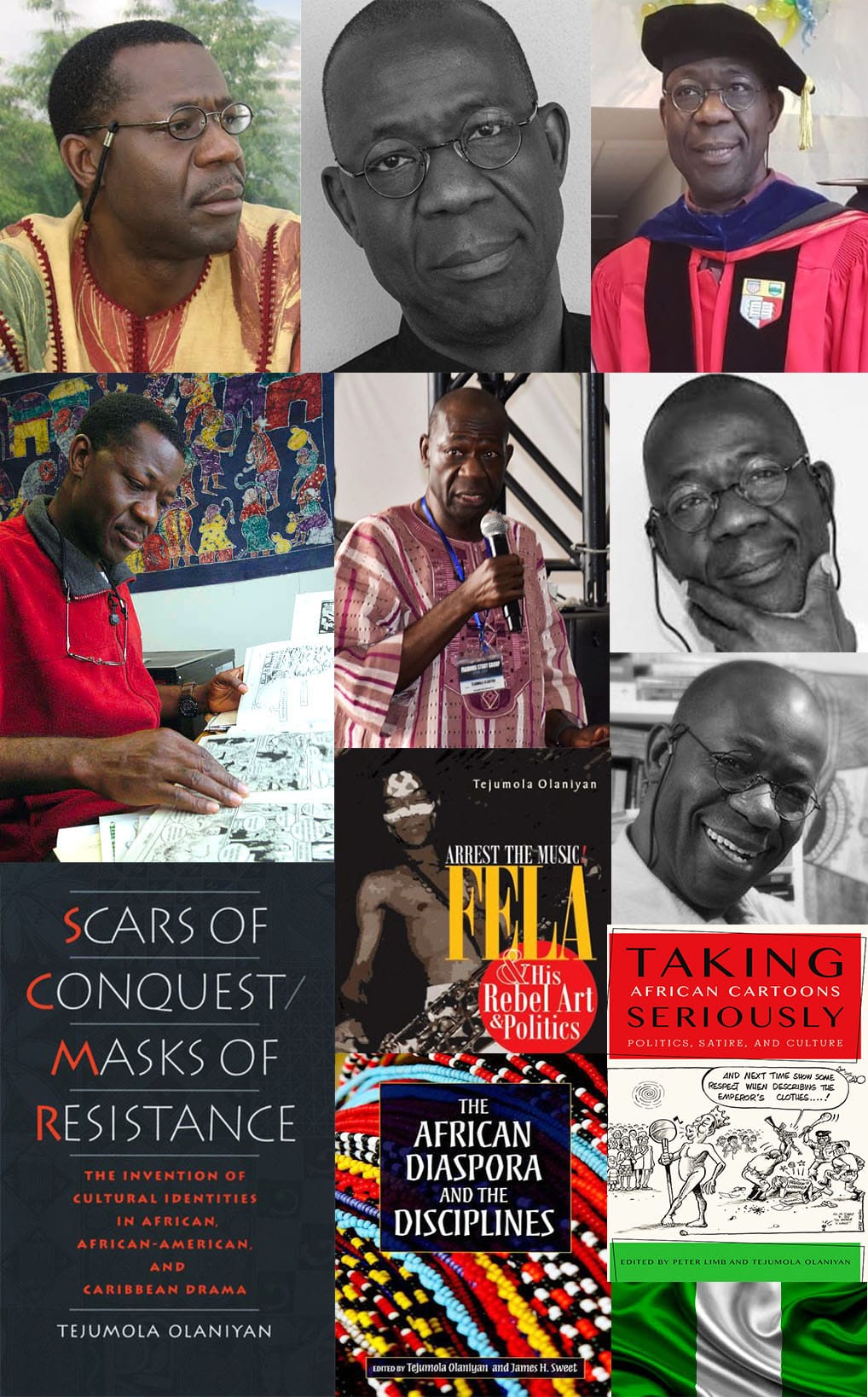

Tejumola Olaniyan passed away on November 30, 2019, at the age of 60. His writing on drama, literature, popular music, and political cartooning redefined the contours of African literary and cultural studies. Indeed, his work has done no less than reconstitute the study of culture in Africa—what it is, how it might be understood—in ways that have inspired countless other scholars and rechanneled the field’s flow of ideas. Olaniyan (Teju or TJ to those who knew him) was Louise Durham Mean Professor of English and African Cultural Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, as well as a recipient of one of the UW’s highest distinctions, a “named professorship” which he claimed in honor of his mentor and first scholarly inspiration, Wole Soyinka.

Teju came from a generation of Nigerian intellectuals who cut their teeth in the embattled field of postcolonial studies. He often remarked that, while he may have mastered the field’s discourse, he did so with a healthy dose of skepticism. Ideally, Teju suggested in another article, the only test capable of determining whether a discourse is truly spoken in the name of Africa is not geographical, or even racial, but ideological. Put simply, “Africa” is an ideological concept, one that emerged along with modernity, but which has also often been the best weapon wielded against it. Among the many legacies of Teju Olaniyan’s teaching and writing would be a project to not only speak in the ideological name of Africa, but to redistribute the power of speaking in that name.

In this interview, Matthew H. Brown, Assistant Professor of African Cultural Studies at the University of Wisconsin‐Madison, discusses Teju's vision, mission and legacy.

1. Allow me to start from a point I should perhaps avoid, when was the first time you met Teju and did it strike you then that this is a person you want to build a professional and personal relationship with?

I was a little familiar with Teju’s work on Soyinka and Osofisan when I applied to the graduate program at Wisconsin. At the time, I wanted to work on Soyinka and was looking forward to meeting him. I first met him when he came to an orientation session in the Department of African Languages and Literature (as it was called then; now it’s called African Cultural Studies). His presence was, to be honest, intimidating. His deep voice, stall stature, and clearly powerful mind made me feel like I was way out of my depth. It took me a while to work up the courage to interact to approach him about my studies, but I knew right away that he was at the very pinnacle of people from whom I could learn a great deal.

2. What’s he like as a teacher? Say a 100 level student walks into Teju’s class, what would be her experience?

I encountered Teju as a (post)graduate student, so I had no expectation of having my hand held. However, I have had discussions with undergraduate students who took his classes—some of whom do expect more hand holding—and their impression was not surprising to me. Many students found him to be a little intimidating. He was not in the habit of showering students with pleasantries or “dumbing things down” to teach a point. The first day in class made some feel like they had chosen something more difficult than they imagined. I even saw some undergraduate students on the verge of tears when he handed graded papers back to them. Regardless, Teju also went out of his way to organize snacks for many of his classes and was open to plenty of creativity when it came to student projects. He deeply cared about students and, most of all, their learning, as well as getting them to do their best work. I know of one person who described Teju as having a hard exterior, but a sweet, sugary center.

3. I saw a tweet in which one of his MA students said she was one of many people “whose lives were revolutionized by Tejumola Olaniyan--to experience research and academic presentations as expressions of love”. A person who only got to know about Teju after he passed might dismiss this comment as hagiography because “revolutionized” suggests some kind of a 180-degree transformation. Speaking for yourself, is there any truth to this? Did you experience any such transformation as Teju’s student?

The student’s expression makes a lot of sense to me. Perhaps my own development was also a revolution, but one that happened slowly. I came to graduate school with a well-developed ability to interpret literature and write essays. I though I could ride that ability to success. From the beginning, Teju often praised my abilities, but he was rarely satisfied with my work and certainly never let me feel satisfied. The idea that research is not only an expression of “love,” but a commitment—a political, social, personal, vow to rigorous critical thinking—resonates with me. Some might consider his standards too exacting, but if you wanted to impress Teju you had commit yourself to the work in way that almost felt like joining an order of devotees whose sole love in life is truth. It can certainly feel like a revolution—if not a revelation—to make such a commitment and find deeper meaning in the work of scholarship.

4. You wrote (https://africasacountry.com/2019/12/reenchanting-teju-olaniyan) “his writing on drama, literature, popular music, and political cartooning redefined the contours of African literary and cultural studies. Indeed, his work has done no less than reconstitute the study of culture in Africa—what it is, how it might be understood—in ways that have inspired countless other scholars and rechanneled the field’s flow of ideas”. It seems like you are talking about some kind of paradigm shift here. Give example of a Teju concept that captures this evolution.

As funny as it may sound, the paradigm shift emerged being very immersed in the current state of affairs, but critically so. It has to do with keeping up with new ideas while never letting go of older ones. In African studies today, there seems to be a lot of one or the other. There are older scholars (and some new ones) who are wedded to anti-colonial and nationalist ideas from the middle of the twentieth century, and there are lots of young people who are pursuing totally new theories and concepts without regard to what came before. Teju was always very insistent that the two must work together. He was courageously intrepid about new forms of culture and new theories, but he always stayed grounded in past ideas. (In fact, he’s somewhat (in)famous for chastising scholars at conference panels, reminding them that the ideas they were throwing around had already been debated and settled long ago, that everyone should know those ideas, and we should take them with us as we move on to new ones.) An example of this dynamic, conceptualized in his work, comes from his book on Fela. To wrestle with the idea that Fela was very “nativist” in his thinking (“African woman no take meat before anybody,” “I be Africa man, original,” “All you Africans, listen to me as Africans,”), but also very cosmopolitan (playing Western instruments and using Western rock and funk conventions, repurposing Western ideas, traveling around the world and collaborating with various artists, singing in English and Pidgin, etc.), Teju invented the concept of “authentic subjectivity.” Scholars have established that “authenticity” isn’t real, that it’s just a way of policing culture. However, when African culture producers strive for it, they may still be doing something important. In the case of Fela, he seems to be both open to the world and yearning for a version of African culture that isn’t dominated by the world. The destination he seeks is not really possible, but it represents the difficult position within which modern Africans find themselves. No person anywhere is free from subjection to power, but perhaps for some Africans the dream is to be free from subjection to outside power, that if the world was really fair there would be forms of power in Africa with which Africans would have to contend, but the same people shouldn’t also be subject to forms of power from former colonists and other global powers. Concepts like “authentic subjectivity” make it possible for our field to both learn from the work of previous scholars but move forward to say more useful things about contemporary culture. There’s a simplicity to such concepts, yet they articulate something that others have grasped at for decades.

5. Teju wrote “asserting African identity, writing back, and recuperating philosophical traditions are meaningless projects unless undertaken in the name of material and cultural redistribution, of creating a world without barriers to both the means of producing and access to knowledge.” Why would an analyst be wrong to dismiss the notion of ‘material and cultural redistribution’ as nostalgia for Soviet era communism?

To be clear, these are my words; an attempt to summarize his spoken remarks at a small symposium in Madison. Teju was trained and worked in a Marxist tradition, though he was not at all orthodox about it. He would have called himself a materialist, meaning that he sees the world of ideas as generated from and responding to material contexts. Another phrase I heard him use more than once was “sociology of knowledge,” the idea that any discourse can be understood as the product of sociological processes. Thus, he was very happy to hear the new generation of scholars talk about decolonizing knowledge and, in the name of that project, promote indigenous African epistemologies, etc., but his reminder to the audience at that conference was that African ideas—and the relative independence and power of those ideas—will spring from the relative independence and power of African people. Thus, in order to promote African ways of knowing the world, we should never lose focus on promoting African material well-being. In one of his conference presentations, he suggested that the countries of the world that built their wealth from the Transatlantic Slave Trade and colonialism should remit billions to African universities, especially in the form of scholarships for African students. If every child in Africa was guaranteed a high-quality university education, or so his theory goes, then African ideas would likely explode into the world. So, though he promoted all kinds of scholarly discourses about Africa, I think he was most devoted to the idea that real resources, distributed to African thinkers and their allies, would generate the best scholarship.

6. Still on that quotation, in what ways did Teju himself work to create a “world without barriers to both the means of producing and access to knowledge”?

Partly included in my response above is his recommendation for an actual policy (though we all know it just an illustrative dream) to redistribute the resources of knowledge production. In his day-to-day work, he was particularly generous—both in time, material assistance, and advice—to scholars from and working in Africa. He was known to go the extra mile to assist African scholars working in the US, and he was also in the regular habit of sending materials to Africa, sometimes hauling them in his own suitcases when he traveled. Whenever it was possible, he assembled African and Africa-based scholars in collaborative projects, such as conferences, edited scholarly volumes, journals, as well as initiatives like the D.O. Fagunwa Foundation.

7. You wrote (https://africasacountry.com/2019/12/reenchanting-teju-olaniyan) Teju’s legacy should include a “project to not only speak in the ideological name of Africa but to redistribute the power of speaking in that name”. Translating Africa from continent to ideology sounds fascinating but might be quite a leap for non-academics like me. What exactly does it mean to speak in the ideological name of Africa and how would such a project work?

In the academic jargon of African studies, we think of Africa not only as a continent, but as construct, or a sign. How did Yoruba-speaking people from West Africa, Swahili speakers from East Africa, Zulu speakers from South Africa, and even Arabic speakers from Morocco, come to think of themselves as “Africans?” How are Black people in the Americas, or anywhere in the world, incorporated into that construct? How did the construct arise? If it was initiated by Europeans during the rise of the modern world, how have Africans reclaimed it for their own purposes? Africa may signify many unrelated and diverse experiences, but it can also be used to unite those experiences into one way of knowing and being in the world—an ideology. To speak in the ideological name of Africa, therefore, is to speak in the name of at least two connected things: the exploitation of African people through the rise of capitalism, the slave trade, colonialism, and neo-colonialism, and the resilience of African people—broadly defined—as they have resisted and contributed to the making of the modern world. Even for non-Africans, the ideology of Africa can serve as a counter-discourse to the spurious universalizing claims of some Euro-Americans.

8. If we take “redistribute the power of speaking” in the “ideological name of Africa” literally, it is easy to assume that diaspora Africans in Euro-American culture and entertainment industry are uniquely placed to serve that purpose. When we look at current story trends in the industry’s motion pictures (Black Panther, et al) and the rising number of African immigrants behind and in front of cameras and microphones in major global production studios, we might even assume that this growing inclusivity will provide ready support for ‘a speaking in the ideological name of Africa’ project. Are these assumptions realistic or overly optimistic?

I think these assumptions are both realistic and include a tendency to being overly optimistic. If you take Marvel’s Black Panther films as an example, they serve as illustrations of the ways African and Black people represent themselves in powerful, liberatory ways that can likely push the needle towards a better, more equitable understanding of Africa’s place in the world. But there are also limitations of course. To pursue Teju’s line of thinking, representing African people and ideas well is part of the project, but actual material change is also necessary. It’s great to see some African and African-descended people on screen, and also getting rich from working in front of and behind the camera on Black Panther, but we might ask what percentage of Disney’s billions in profits actually goes to Africa and Africans? It seems unlikely that Black Panther changes much about the distribution of wealth. That isn’t to say that money is the only thing that counts, however. At the end of the day, material redistribution and representational redistribution work together. It may very well be the case that greater knowledge and understanding of Africa and Blackness, produced in the media, will lead to greater material investment in both.

9. Listening to your interview on https://newbooksnetwork.com/indirect-subjects, I have to say that I, and I’m sure many diaspora Nigerians, find your description of the condition you named periliberalism spot on. It conjured in my mind a primordial image, that of the grim life of worker ants whose entire life story is birth, work and death. This, unfortunately, is the fate of Nigerians who, as you said, are marginalized from the process and profit of capitalism. I couldn’t get past that image even when you talked about New Nollywood and the influx of transnational capital, it seems like Nollywood’s rising status as a global culture phenom is not rubbing off on the marginalized Nigerians. Does Nollywood have a role in the grand scheme of ‘speaking in the ideological name of Africa’.

This is a very astute question that goes to the heart of my research. Among those who study and observe Nollywood closely, there are debates—and perhaps internal contradictions—about Nollywood’s role in ‘speaking in the ideological name of Africa.’ Part of what made Nollywood so successful is that, contrary to other cinema traditions on the continent, Nollywood put politics on the back burner and aimed solely at entertaining a local audience. To do so well, however, the industry had to tap into the desires, fears, and dreams of that audience. In both representing and commenting on those desires, fears, and dreams, a film industry cannot help but speak in ideological terms. What do people want from the world? What can they expect? How should they go about getting it? What is a good method to do so and what is not? These ways of framing what is possible and how it can be pursued are fundamentally ideological. They represent a particular understanding of how the world works—an understanding shaped by historical experience, government propaganda, the education system, religion, international media, the local economy, etc., etc. Early Nollywood, even if it put overt politics on the back burner, dealt with these issues in interesting ways that often included both a subtle critique of the world order and resignation to some things that don’t seem changeable. I believe these messages invited the local audience to understand the world in a complicated way. As New Nollywood pursues global audiences through platforms like Netflix, will it continue to embed subtle critiques of the way our world works, or will it increasingly suggest that the world is open to everyone (especially highly-educated and well-resourced Africans). If so, how is Nollywood inviting marginalized Nigerians to think about our world? Is it speaking to them and their desires, or past them?

10. UW Madison’s Department of African Cultural Studies was known as the Department of African Languages and Literature from 1964 to 2014. The processes of instituting cultural studies as the frame for the Department’s academic endeavors commenced in 2015 and ended in 2018 under Teju’s leadership. Was Teju able to deliver on the promises and practice envisioned for the re-birthed Department? How?

Part of the reason the department changed its name is that it was already producing a lot of cultural studies work, rather than the old-fashioned philological work suggested by “languages and literature,” and Teju was central to those developments. His research on Fela and political cartooning is much closer to cultural studies than literary studies. More importantly, he excited a generation of students to pursue cultural studies topics (including me!). Indeed, one of Teju’s great qualities was that, even though he was one of the most rigorous and erudite scholars in our field and at our university, he was always encouraging and promoting others. So, in his time as a leader in our department, he brought in many new graduate students, junior faculty, and even senior faculty from other departments to contribute to shaping our understanding of African cultural studies. That legacy still very much exists today. Ours is an eclectic and diverse department that Teju played a major role in shaping.

11. Teju was awarded the WARF professorship which he named after Wole Soyinka, his teacher and mentor. It is said to be one of the highest honours UW Madison has to bestow. Explain the significance of the award, what does it say about his scholarship, what does it say about his service to UW and the wider community of academics?

The WARF professorship is reserved for senior faculty who have had a major impact on their field. Very few are awarded and they come with not only recognition, but a very generous allocation of research funds (more generous than most of us in the humanities will ever see). The funds signify that the awardee has delivered transformational research in the past and will continue to do so in the future. A faculty member cannot apply directly for the funds, but must be nominated by their department. In Teju’s case, the English department, one of the biggest humanities departments on campus, found him to be particular deserving.

12. Teju left his alma mater, University of Ife, and Nigeria in 1987 but his experience at Ife and Nigeria have fueled his work at Madison and elsewhere. Nigerian academia, and society, have since suffered a lot of structural and resource deficiencies that constrain access to the fruits of his scholarship. Many diaspora Nigerians hope the recently launched Tejumola Olaniyan Foundation will bridge that gap. From your vantage point as Teju’s colleague and professor with research interest in Nigeria, what would you recommend the Foundation does to establish and sustain a relationship with students and the academia in Nigeria?

I have been closely watching and in some cases involved with the launching of the Tejumola Olaniyan Foundation, so perhaps I’m a little biased. There are many things the foundation can do, from providing funds not only to students and academics, but also to culture producers like aspiring writers and filmmakers. More importantly, the way the foundation provides funds can be tailored to foster the transnational movement of resources and ideas. For example, scholarly publishing still suffers from geographical divides. It’s difficult for those of us in the US to get access to many books and journals published in Africa, and vice versa. Foundation grants can help Africa-based scholars publish in North American and European venues. They can also help make knowledge published in North America and Europe more available to Africans. For example, at a panel during last year’s Lagos Studies Association conference, one scholar lamented that my book, Indirect Subjects, is not available for purchase in Nigeria. To make it available online for download anywhere--for free, which I would love to do—I would require me remit a very large sum (more than I can personally afford) to my US-based publisher. Funds from the Foundation can make such things possible. More importantly than helping US-based scholarship reach Africa, it can help Africa-based scholarship reach the US. It can fund workshops on writing for international journals and university presses, and can even help connect Africa-based scholars with international publishers. I should also note that, currently, the Foundation is helping many US-based scholars from Africa (such as Nigerian students studying in the US) fund research travel to Africa. Those scholars often don’t have access to certain funds to which American citizens have access. Such funding can ensure that they stay connected to the Nigerian academy. Hopefully, it can work the other way too.